According to the Financial Times, in this article, it was just 5 years ago that Raiffeisen International, the Austrian-based bank with the greatest involvement in Eastern Europe, bought Casa Agricola, a struggling state-owned Romanian bank, for $45m and invested about $250m in its modernisation. Today, analysts estimate the bank could be sold for $2.5bn (€1.68bn, £1.22bn). The rise in value is attributed to Raiffeisen’s success in overhauling Casa Agricola as well as to Romania’s soaring economic growth, rapid credit expansion and spiralling asset appreciation. Many business people in Bucharest see the case of Casa Agricola as exemplary, and argue that similar success stories are developing across the board.

Not everyone, however, sees things like this. The International Monetary Fund, for example, (and of course yours truly the blogger here) takes a rather different point of view. Concerned about the continuing impact of the global credit market turmoil, the IMF has been consistently warning (and here) about the dangers of economic overheating in Romania, citing in particular the yawning current-account deficit and the financing problem that this could pose should there be a sudden and sharp reversal in investor risk appetite.

In addition inflation, which had been falling steadily in recent years, jumped to 6.8 per cent October after climbing steadily from a low around 4 per cent in the January-July period.

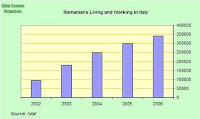

Rising world energy and food prices, compounded by a drought inside Romania itself, are playing their part. But so is rapidly rising local pay (fuelled in part by labour shortages which are caused by massive outmigration - the consequences of which the Romanian authorities are effectively in denial about - and years and years of below replacement fertility). Wages seem set to rise this year by about 25 per cent in money terms (or about 20 per cent in real terms) year on year.

Far from running a fiscal surplus to try and cool the economy - as advised by the IMF to drain excess liquidity from the system - government spending is being increased, with a 43 per cent increase in pensions currently being implemented, and a further 30 per cent rise having already been approved for early 2009.

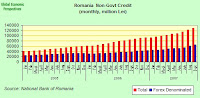

A steady and increasing flow of remittances from Romanians working abroad is also helping to fuel a credit surge, particularly in home loans. In fact the IMF is not the only entity drawing attention to this situation. The National Bank of Romania published data earlier this week - in its Monetary indicators October 2007 press release - which shows that private debt in Romania increased an annual 51.4 percent in October as individuals and companies took out more loans in foreign currencies. Debt rose to 133.3 billion lei ($55 billion) as of Oct. 31.

And the combination of all these factors means that GDP goes charging forward at what may well be an unsustainable pace. According to data just released from INSSE (the National Statistics Office) GDP in Q3 2007 again accelerated again (slightly) to an annual 5.7 %, up from 5.6% in Q2.

Now according to the Romanian National Bank:

In October, non-government credit went up 3.3 percent (2.3 percent in real terms) from September 2007 to RON 133,319.6 million. RON-denominated loans picked up 3.3 percent (2.3 percent in real terms), while foreign currency-denominated loans increased by 4.0 percent when expressed in EUR and by 3.3 percent when expressed in RON. At end-October 2007, non-government credit advanced year on year by 51.4 percent (41.7 percent in real terms) on the back of the 40.5 percent growth in RON-denominated loans (31.5 percent in real terms) and the 63.3 percent rise in foreign currency-denominated loans expressed in RON (when expressed in EUR, forex loans expanded by 72.4 percent).

The IMF has warned that borrowers might be assuming too much risk, especially as an increasing share of the loans are either in foreign currency, mainly euros, or indexed to foreign currency.

And of course all this increase in credit is financing soaring increases in imports, boosting this year’s likely current account deficit to 14-15 per cent of GDP – a level the IMF considers dangerous. Last year the €10bn deficit was largely financed by privatisation-boosted FDI of €9bn. But this year’s forecast FDI of €7bn will fall far short of the likely €17bn deficit – leaving banks to finance the gap with credit, much of it short-term.

The IMF take the view that this is unsustainable, particularly with global conditions worsening. But Bucharest-based bankers argue much of the credit is quasi-investment as it is provided in-house by multinational banks to their Romanian subsidiaries.

Of course one of the areas where all this extra economic heating is most directly noticed is in construction, and Romania recorded in August (the latest month for which comparative data are available from Eurostat) the highest annual pace of construction growth (37.5%) of any country in the European Union. According to data supplied to Eurostat, Romania is way out in front here, followed by Great Britain with a 7.7% year on year rate and Slovenia with a 4.6% one. Even the Baltic countries have no dropped out of this particular race.

Meanwhile the Romanian leu continues its downward course, falling again early in the week for the third straight week against the euro as investors became increasingly concerned about the widening current-account deficit and accelerating inflation. The leu has been the world's worst-performer against the euro in recent weeks, falling the most since August 2005, as investors trended away from higher-yielding emerging-market assets amid a sell-off in Romanian stocks.

As can be seen above, in the few days the fall seems to have been brought to at least a temporary halt after central bank Governor Mugur Isarescu said sharp swings in the exchange rate can harm the country's economy and indicated the possibity of a further tightening of monetary policy to address the inflation problem.

The National Bank of Romania raised its key interest rate to 7.5 percent from 7 percent at the end of October following the rise in the inflation rate to a one-year high of 6% in September and 6.8% in October. But Isarescu has also warned about the sharp rise in indebtedness and the limits to conventional monetary policy in the current environment.

"In the last four or five months, credit in foreign currencies exploded...When we raise rates, foreign currency loans rise because they look cheaper. We have reached a limit of monetary policy.''

Romanian Central bank Governor Mugur Isarescu

Now although Romania nominally has a relatively high unemployment rate - some 7% using ILO methodology - it is impossible to know just how realistic this figure is, since we do not really know how many Romanians are actually in the country and ready and available for work, or indeed the quality of the unemployed labour force that actually are. One measure of the situation though can be found in the recent statement by economy and finance minister Varujan Vosganian that Romania has a current labor shortage of about 500,000 workers, especially in construction, heavy industry and car manufacturing.

"We need more engineers, mechanics and bricklayers........We have a labor deficit of about 500,000 employees," he admitted at the opening of a conference on professional and technical education recently.

One of the really difficult problems which comes into operation in a situation like that which Romania is currently experiencing, and where a strong level of euro indexing of prices and a significant number of households and companies are paying loans which are in or indexed-to euros (or other foreign currencies), is that exchange rate and monetary policy become effectively impotent (this is what Mugur Isarescu means when he talks about the limits of monetary policy) to correct growing competitiveness problems - since given the indebtedness it is just not practical to encourage any substantial downward correction the exchange rate, while increasing the interest rate only puts upward pressure on the currency and attracts additional funds in search of yield, and these only serve to make the excess demand problem even worse. Thus the only real arm left in the government policy arsenal is the fiscal policy one, whereby the government attempts, by running a fiscal surplus, to "drain domestic demand" from the system, and thus work to effect some form of price deflation (for a fuller discussion of this complex topic in the Latvian context see this post). And this, of course, is exactly the policy that the IMF economists tirelessly advocate that the Romanian government practices, but unfortunately the message seems to be falling on deaf ears.

Now, evidently, running a deficit stimulates demand, which increases economic growth, and this extra growth does, of course, bring in increased revenue which can help pay for extra spending, but if the economy is already running up against its capacity limits then this extra growth is rather artificial, and such attempts at growth really only has one result, that of pushing up wages and prices, and thus increasing inflation, and given the difficulties associated with implementing a strong downward correction in the currency this inflation means only one thing, a loss of export competitiveness, and this, of course, is what we are seeing happening in the Romanian case.

And on top of this we have the issue of remittances coming back home, stimulating even more demand, demand which would lead to the employment of those workers who have migrated, only they are now no longer there. Undoubtedly this flow of remittances (around 4.3% of GDP in 2006 according to the World Bank) carries some of the responsibility for the escalating home demand, and rush to borrow, since you don't have to be an economic wizard to see that the money can be initially used to accumulate the deposit to purchase a new family home, and then subsequently as a stream of income to help make the mortgage repayments.

So more than having the alarm bells ringing, the writing is now on the wall I would say. Even Central bank Governor Mugur Isarescu warned on Nov. 1 he was concerned that foreign-currency lending ``exploded'' in recent months, increasing the risk associated with any depreciation of the local currency, and the national currency the leu was the world's worst-performer against the euro last week, falling the most since August 2005, as investors shunned higher yielding emerging-market assets amid a sell-off in Romanian stocks. So take note of the old adage, caveat emptor.